Crazy people: part 2

18. Jul ’17

General

This month we do feature some adventure stories from our friends and customers.

Last week you could read about the world record of the two Bikingmen Axel and Andreas.

This week we have a different "suffering experience" from Ultan. Ultan works for Rapha and was at our office two weeks ago for a presentation about the pedaled transcontinental race. In the way Ultan spoke about this adventure - that happened almost a year ago - you could feel that the positive and negative emotions where still alive as if it just happened yesterday.

Enough said, here is what Ultan has to say about one of the hardest unsupported sports effort in this world (or have you ever seen a soccer player playing for 10 days in a row?) And yes, the gallery is small but there is no time to take pictures if you compete on Ultan's level.

"The Transcontinental is a race that embraces individualism from the very start. From Geraardsbergen in Belgium to the historic port of Çanakkale in Turkey, via four strategically placed checkpoints, riders are free to choose their own route, taking them on a journey averaging 3,800km with 50,000m climbing by the time they reach the finish line.

But the freedom is part of the challenge – and accounts for many a riders’ downfall. This is not a UCI governed event, so apart from 10 simple rules you are allowed to ride as you wish. Bar a tandem or a recumbent, you can ride any bike, no guidance is given on what you should or shouldn’t do, and friends and family aren't allowed to help if you run into trouble.

In 2015, when I rode it for the first time, I chose to ride a time-trial bike. Partly because I had spent a lot of time training and racing on it, and partly because I knew I needed to find some kind of advantage over the favourites, who were veterans of the race.

But my freedom to choose proved problematic. I fell short on the rough roads and the tight gaps between the frame and the tyres meant I could only run a 23mm on the rear. Stick on an additional 5kgs of kit and bounce around some rough roads, and bang, bang, bang. Puncture fest.

I didn’t count how many punctures I got last year, but it was definitely more than 10. Each one leaves you nervous on anything that isn’t fresh asphalt, and on the notoriously unpredictable roads through the Balkans each blowout left me jittery.

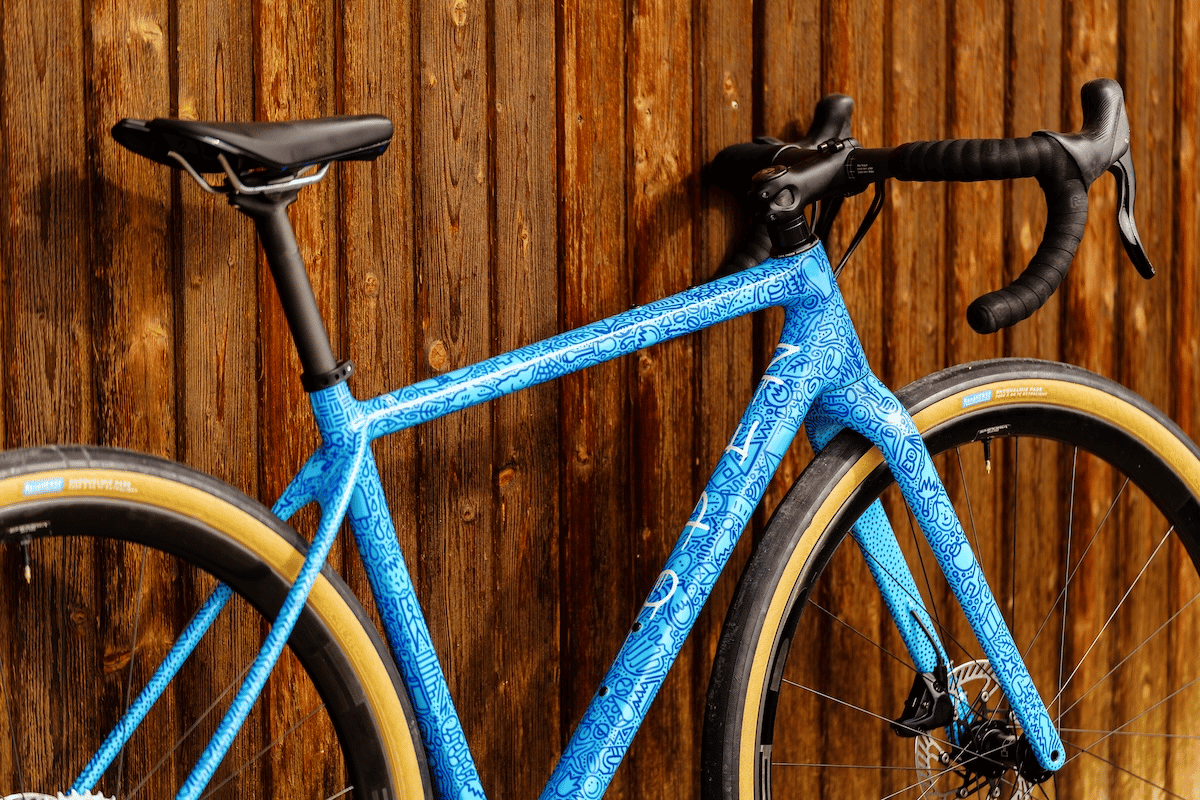

But, another year, another race. When I first rode an Open UP in January, it was an instant click. I was bouncing off kerbs and detouring down bridleways on my first outing, already thinking this was the machine for the Transcontinental 2016.

It ticked all the boxes: lightweight to support all the climbing, disc brakes that would prove particularly useful in testing Alpine weather, great tyre clearance for loose roads, good frame bag accommodation with low mounted bottle cages.

Rolling off from the startline this year I was a lot calmer knowing that I was ready for all eventualities. So calm, in fact, that I had to stop for a sleep after five hours as my eyes wouldn’t stay open.

The first few days were a challenge of the mind. My route planning turned out to be on the scenic side. I had mapped it all out via the cycling function RidewithGPS, a schoolboy error which presented me with all manner of farm tracks to negotiate. Although I had the right bike for it, I knew the scenic option wasn’t going to be the fastest and it duly saw me drift from the front of the race.

In the 2015 edition I quickly realised that any weakness or bad planning is exposed. You can’t fluff your way through this race, you can’t even fluff your way through the first couple of hundred kilometres. Every cut corner in your preparation comes back to haunt you, somewhere along the way.

I eventually arrived at CP1 in Clermont-Ferrand in around 15th position, with about 2-3hrs of sleep in hand. I overheard that all other riders bar 3 or 4 were sleeping so if I continued I’d be 5th on the road. I couldn’t resist the chance to claw back some time, so I headed back out onto the road.

This worked well – until the sleep deficit caught up with me. I took a wrong turn before just before the Swiss border, and although it was relatively easy to get back on course, mistakes like that take a psychological toll: thoughts of the additional climbing I added, extra miles and positions lost was a mental challenge to get my head around.

The next day followed a similar pitch. Righting wrongs with navigational errors and trying to alter routes on the fly. It can really wear you downne when you keep making mistakes, but there comes a point when that phase passes and you start finding your flow again. You have to stop stressing about what you have or haven’t done and focus on the present. Some days you are up, and some days you are down, and as soon as you think you have the hang of it something will arise to test such arrogance.

So after the first three days of hiccups I settled into it. I realised the front of the race had gone, and once I removed that pressure from the equation the race became more enjoyable. One of the highlights was riding up the Grimsel and Furka Passes around midnight listening to Ice Ice Baby. Granted, I probably missed out on a beautiful spectacle, but having the whole place to myself was magical (and I enjoyed not been able to see the gradient).

The next drama came as I was descending towards CP4 at the foot of the Gavia Pass. I was 10k or so from the checkpoint when I was greeted by a great big barricade. Backing up was not an option. I decided to clamber over and hope for the best. I managed to straddle the first fence find then I was greeted by the second one. The boys who set this one up most have been proud of its impenetrability. A sheer drop to the left and concrete wall to the right. It was too high to climb with the bike and too well set to crawl under. The only option was to hike around.

In the end I headed over to the rock edge to see if I could climb down. Cycling shoes are terrible for bouldering, so too is carrying a bike. Luckily, two cyclists came past. I cried for help. They managed to guide me down and if it wasn’t only for their assistance I would surely have broken either bike or limb or both.

Once I got down I was high as a kite. My pearly white shoes were covered in goat shit, my bibs ripped and my legs and arms scratched all over, but I was pedalling again.

The next few days were spent battling and hiding from the heat, and things didn’t change again significantly until I hit the Balkans where the weather took a turn. By the time I hit Macedonia, I could smell the lightning. It was striking all around me and I was terrified. Torrential rain, deafening thunder, the smell of electricity and me cycling along a Macedonian motorway. That experience will stay with me for a while. I found refuge in a service station where the staff let me sleep in a disused shower. It may sound like squalor but it was like a 5-star hotel that night.

Greece was a welcome sight. The temperature started to rise again and the wind picked up too. Just what you need after 3,000-odd kilometres of riding – 40-45ºc and a 30mph headwind. I saw a few belly scratching locals hiding from the heat at a bar/shed/caravan and I pulled up to join them. They were in no rush to do anything so I happily nestled myself amongst them and soaked it up. It took maybe an hour to get a sandwich.

As night drew in I knew I needed to capitalise on the cooler temperatures and press on for Turkey. I saw a digital temperature reading of 27.5ºC at midnight. That was another highlight, the atmosphere flowing through Greece during the night with packs of dogs chasing you down every now and then. Some people hate the dogs but I love the buzz of them chasing you. It’s like two shots of adrenalin administered to each calf muscle. I’m generally quite scared of dogs, but by the time I meet them on the race I’ve turned almost feral myself.

It was a dash for the line the next day. Nelson Trees, another rider who I’d been neck and neck with for some time, and I crossed the Turkish border together and shooked hands to signify “may the best man win” in the 120km race to the finish line. I slipped into time trial mode and managed to hold him off to the line with 10mins to spare. I finished 6th in the end.

Fitness is only a small part of this race. It’s about resilience in the truest sense of the word: the ability to recover in times of difficulty; but also the ability to spring back into shape after infinite mountains and sleepless days and nights. To have a bike that can be as resilient as its rider in their toughest and bravest moments, but one that can keep carrying and coaxing them through in moments of despair, wrong turns and weakness, is a triumph."

Last week you could read about the world record of the two Bikingmen Axel and Andreas.

This week we have a different "suffering experience" from Ultan. Ultan works for Rapha and was at our office two weeks ago for a presentation about the pedaled transcontinental race. In the way Ultan spoke about this adventure - that happened almost a year ago - you could feel that the positive and negative emotions where still alive as if it just happened yesterday.

Enough said, here is what Ultan has to say about one of the hardest unsupported sports effort in this world (or have you ever seen a soccer player playing for 10 days in a row?) And yes, the gallery is small but there is no time to take pictures if you compete on Ultan's level.

"The Transcontinental is a race that embraces individualism from the very start. From Geraardsbergen in Belgium to the historic port of Çanakkale in Turkey, via four strategically placed checkpoints, riders are free to choose their own route, taking them on a journey averaging 3,800km with 50,000m climbing by the time they reach the finish line.

But the freedom is part of the challenge – and accounts for many a riders’ downfall. This is not a UCI governed event, so apart from 10 simple rules you are allowed to ride as you wish. Bar a tandem or a recumbent, you can ride any bike, no guidance is given on what you should or shouldn’t do, and friends and family aren't allowed to help if you run into trouble.

In 2015, when I rode it for the first time, I chose to ride a time-trial bike. Partly because I had spent a lot of time training and racing on it, and partly because I knew I needed to find some kind of advantage over the favourites, who were veterans of the race.

But my freedom to choose proved problematic. I fell short on the rough roads and the tight gaps between the frame and the tyres meant I could only run a 23mm on the rear. Stick on an additional 5kgs of kit and bounce around some rough roads, and bang, bang, bang. Puncture fest.

I didn’t count how many punctures I got last year, but it was definitely more than 10. Each one leaves you nervous on anything that isn’t fresh asphalt, and on the notoriously unpredictable roads through the Balkans each blowout left me jittery.

But, another year, another race. When I first rode an Open UP in January, it was an instant click. I was bouncing off kerbs and detouring down bridleways on my first outing, already thinking this was the machine for the Transcontinental 2016.

It ticked all the boxes: lightweight to support all the climbing, disc brakes that would prove particularly useful in testing Alpine weather, great tyre clearance for loose roads, good frame bag accommodation with low mounted bottle cages.

Rolling off from the startline this year I was a lot calmer knowing that I was ready for all eventualities. So calm, in fact, that I had to stop for a sleep after five hours as my eyes wouldn’t stay open.

The first few days were a challenge of the mind. My route planning turned out to be on the scenic side. I had mapped it all out via the cycling function RidewithGPS, a schoolboy error which presented me with all manner of farm tracks to negotiate. Although I had the right bike for it, I knew the scenic option wasn’t going to be the fastest and it duly saw me drift from the front of the race.

In the 2015 edition I quickly realised that any weakness or bad planning is exposed. You can’t fluff your way through this race, you can’t even fluff your way through the first couple of hundred kilometres. Every cut corner in your preparation comes back to haunt you, somewhere along the way.

I eventually arrived at CP1 in Clermont-Ferrand in around 15th position, with about 2-3hrs of sleep in hand. I overheard that all other riders bar 3 or 4 were sleeping so if I continued I’d be 5th on the road. I couldn’t resist the chance to claw back some time, so I headed back out onto the road.

This worked well – until the sleep deficit caught up with me. I took a wrong turn before just before the Swiss border, and although it was relatively easy to get back on course, mistakes like that take a psychological toll: thoughts of the additional climbing I added, extra miles and positions lost was a mental challenge to get my head around.

The next day followed a similar pitch. Righting wrongs with navigational errors and trying to alter routes on the fly. It can really wear you downne when you keep making mistakes, but there comes a point when that phase passes and you start finding your flow again. You have to stop stressing about what you have or haven’t done and focus on the present. Some days you are up, and some days you are down, and as soon as you think you have the hang of it something will arise to test such arrogance.

So after the first three days of hiccups I settled into it. I realised the front of the race had gone, and once I removed that pressure from the equation the race became more enjoyable. One of the highlights was riding up the Grimsel and Furka Passes around midnight listening to Ice Ice Baby. Granted, I probably missed out on a beautiful spectacle, but having the whole place to myself was magical (and I enjoyed not been able to see the gradient).

The next drama came as I was descending towards CP4 at the foot of the Gavia Pass. I was 10k or so from the checkpoint when I was greeted by a great big barricade. Backing up was not an option. I decided to clamber over and hope for the best. I managed to straddle the first fence find then I was greeted by the second one. The boys who set this one up most have been proud of its impenetrability. A sheer drop to the left and concrete wall to the right. It was too high to climb with the bike and too well set to crawl under. The only option was to hike around.

In the end I headed over to the rock edge to see if I could climb down. Cycling shoes are terrible for bouldering, so too is carrying a bike. Luckily, two cyclists came past. I cried for help. They managed to guide me down and if it wasn’t only for their assistance I would surely have broken either bike or limb or both.

Once I got down I was high as a kite. My pearly white shoes were covered in goat shit, my bibs ripped and my legs and arms scratched all over, but I was pedalling again.

The next few days were spent battling and hiding from the heat, and things didn’t change again significantly until I hit the Balkans where the weather took a turn. By the time I hit Macedonia, I could smell the lightning. It was striking all around me and I was terrified. Torrential rain, deafening thunder, the smell of electricity and me cycling along a Macedonian motorway. That experience will stay with me for a while. I found refuge in a service station where the staff let me sleep in a disused shower. It may sound like squalor but it was like a 5-star hotel that night.

Greece was a welcome sight. The temperature started to rise again and the wind picked up too. Just what you need after 3,000-odd kilometres of riding – 40-45ºc and a 30mph headwind. I saw a few belly scratching locals hiding from the heat at a bar/shed/caravan and I pulled up to join them. They were in no rush to do anything so I happily nestled myself amongst them and soaked it up. It took maybe an hour to get a sandwich.

As night drew in I knew I needed to capitalise on the cooler temperatures and press on for Turkey. I saw a digital temperature reading of 27.5ºC at midnight. That was another highlight, the atmosphere flowing through Greece during the night with packs of dogs chasing you down every now and then. Some people hate the dogs but I love the buzz of them chasing you. It’s like two shots of adrenalin administered to each calf muscle. I’m generally quite scared of dogs, but by the time I meet them on the race I’ve turned almost feral myself.

It was a dash for the line the next day. Nelson Trees, another rider who I’d been neck and neck with for some time, and I crossed the Turkish border together and shooked hands to signify “may the best man win” in the 120km race to the finish line. I slipped into time trial mode and managed to hold him off to the line with 10mins to spare. I finished 6th in the end.

Fitness is only a small part of this race. It’s about resilience in the truest sense of the word: the ability to recover in times of difficulty; but also the ability to spring back into shape after infinite mountains and sleepless days and nights. To have a bike that can be as resilient as its rider in their toughest and bravest moments, but one that can keep carrying and coaxing them through in moments of despair, wrong turns and weakness, is a triumph."