Developing new models

29. May ’19

General

This is what I wrote in December 2018, when it wasn't looking so hot for one of the new models we're working on:

Business is going well, so nothing to complain about you'd think. ONE+, UP and UPPER sales continue to growth, we're still managing to do that with just selling framesets, so it should be relatively simple. Despite that, the past months have been very frustrating, even to the point that maybe for the first time, there's been some irritation creeping in between Andy and I.

We've been working on two new models in parallel for quite some time now. Don't get your hopes up, this is nothing out of the ordinary and doesn't mean two new models will ever see the light of day. To give you an idea, the project names for these two are OPN-11 and OPN-12, meaning they were proceeded by 10 other projects. And yet there are only three models in the history of OPEN, the other seven projects were abandoned.

We've been working on two new models in parallel for quite some time now. Don't get your hopes up, this is nothing out of the ordinary and doesn't mean two new models will ever see the light of day. To give you an idea, the project names for these two are OPN-11 and OPN-12, meaning they were proceeded by 10 other projects. And yet there are only three models in the history of OPEN, the other seven projects were abandoned.

You might argue that's a terrible score, 70% failure! And I presume it is, the way people (including myself) are wired nowadays. We profess to love risk taking and risk takers, as long as they succeed. But of course if success is guaranteed, it's not risk-taking! Even if you say "well, I love the risk takers who succeed because they clearly have something extra, others in their place would have failed", that still means they weren't taking a risk, they were merely taking a direction that would have been risky for others. So they might be very skilled, they might be visionaries, but not risk takers.

Anyway, enough philosophizing. And we're not exactly saving the world here, we're just designing bikes, trying to do that a bit differently and that means that from time to time it doesn't work out. Of course it also helps (or hurts) that we have the freedom to abandon projects, that we don't have bean counters telling us "you've spent a couple hundred grand on this project, you have to bring out something to earn it back".

Back to the story, the OPN-11 was very close to production. It's a model I am very excited about, a nice addition to the line-up and very different from what exists in the market.

Then just one week to pilot production start, Andy sends me a note: "Big problem, the chain touches the dropout". I can't understand it, but see the proof on Skype. We measure everything, but it seems within spec. I check the CAD, all good. We try a different rear wheel, it works. Of course that doesn't mean anything, there are lots of different wheel specs. We try the offending wheel in an UP, it works. But that dropout design is meant to have different clearances, so it doesn't mean much either. I'm going crazy! Two days later the solution, it's not our frame that is faulty, it's the cassette. Somehow it had a lip on it that prevented it from fully sliding onto the cassette body. What are the odds of a standard production cassette, produced by the hundreds of thousands, has one that is faulty and that happens to be the one that makes it into our frame-check stock? Very small I'd think, but I am happy this one was. Phew.

A few days later, another note: "Big problem, crank X doesn't fit". What the heck, how is this possible? We know not "everything" fits, we always play with clearances and design around a specific group of cranks, but this crank should fit, Yet its chainring wants to go where our chainstay sits. We call the crank maker, check the clearances, and confirm it should be no problem. It should have the same chainline as crank Y but yet that crank has tons of clearance. We check spacers, BBs, everything, again it doesn't make sense. Even more strangely, when we put a bigger chainring on, the clearance gets better!

Finally the crank maker comes back to us: sorry, the chainring was an old design, it somehow slipped through, and just by chance made it to us and we happen to have made it the one crank to answer all questions. We get the correct chainring, it all works.

So we sign off on the start of the pilot production. The next day I wake up to an email from Andy: "We have a big problem". With a Force/Eagle AXS setup, the chain hits the chainstay. I'm not worried anymore, I'm sure it's a false alarm again. But on Skype I cannot deny it looks bad. It's not off by a little, it doesn't fit AT ALL.

I can't understand it, there is nothing special about that combination other than that it's new (meaning we didn't have the chance to try it before). But it should have more clearance with its long cage, not less. I'm frustrated beyond belief, this model could have been on the market within 3 months and now it's back to "indefinite". Is it the drivetrain parts that are wrong, or is it really the frame?

I feel Andy is frustrated too, and although he doesn't say so, I really feel this one is on me. I'm the one responsible for the designs, I should have caught this, but at the same time I am not sure how since none of our models indicated this combo could be an issue. And worse, I don't really see a solution.

For Andy it is maybe also a a bit of death by a thousand paper cuts. Because he does all the operations, most of the problems land on his shoulders. Delays in production, problems with retailers, a shipment stuck in customs, a painter gone mad, accounting (of any type), he has to deal with that while I get to play with bike designs. In my mind, I keep hearing "You had one job!!!!"

I take four hours just to sit on the couch while my mind is racing, and come up with two possible solutions. One that would save most of the molds and fixtures we have already made (about 30 in total), and one that would be better but would require most of the tools to be either modified or scrapped completely, which would obviously increase the costs but also the timeline to completion.

As I sketch it out and start working through the two options with our CAD designer, the second option starts to look better and better, in fact the frustration gives way to excitement. The new design is better than the old, and just before midnight we have the design ready. Off to the factory, so they can see if it is feasible, and I go to bed. The next morning, the factory is enthusiastic, they say they can probably make the new molds and the layup changes in six weeks, not as bad as I feared. They don't have the bill yet for what all the changes will cost, that's a part I am definitely not excited about. But to be fair, the success of the UP allows us to take risks even if it means we sometimes are presented with an unwelcome bill.

I show Andy the new design on Skype and share my excitement. I really am way more pumped about OPN-11 now than a week before. He tells me he had lost his excitement for this "model of hell", but with some workarounds he took the prototype OPN-11 for a ride and he is now really gung-ho again.

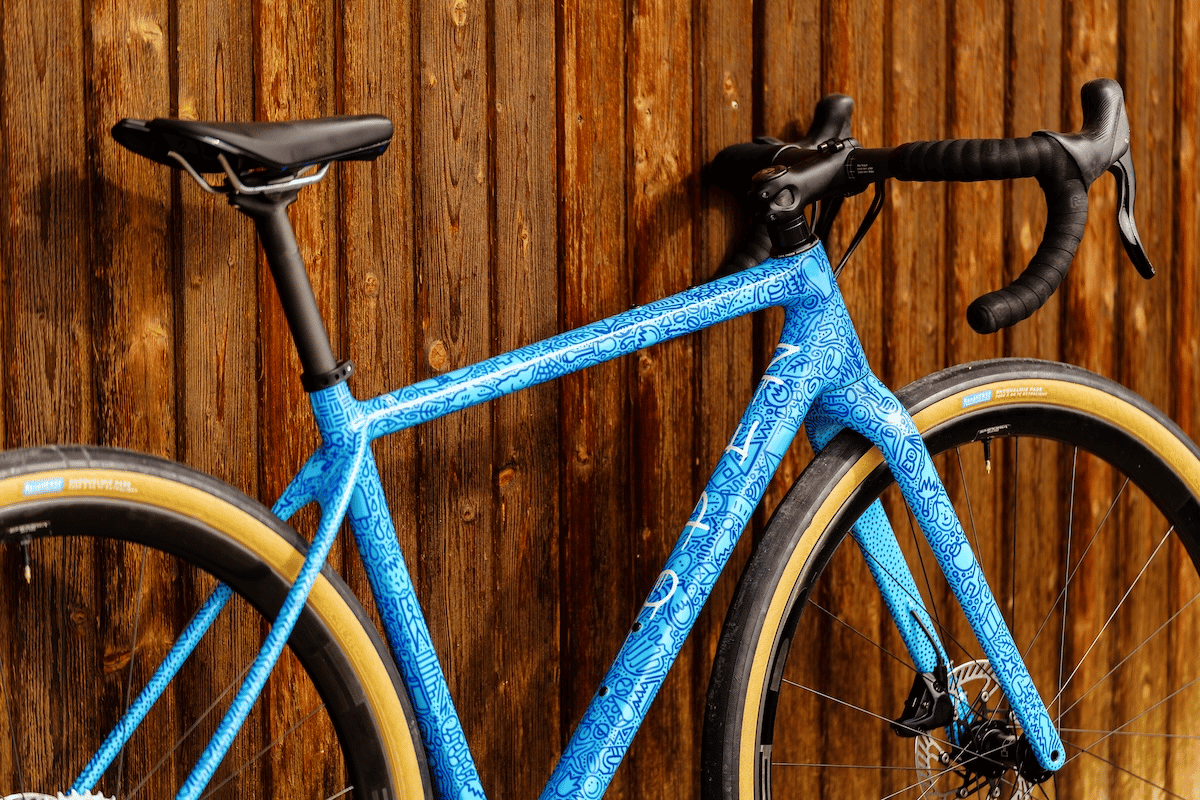

That day, our "resident videographer" happened to be in Basel because we thought we were going to shoot the final bike, so he went along for the ride and even took his drone. It was very cold but the snow was no match for the OPN-11. This was the result:

That day, our "resident videographer" happened to be in Basel because we thought we were going to shoot the final bike, so he went along for the ride and even took his drone. It was very cold but the snow was no match for the OPN-11. This was the result:

And here we are, a few months down the road, a few days away from launch. And for the first time since December, I read this post again. Although I can still feel the anxiety from the week I just described, I also feel proud that the OPN-11 is finally ready. More coming soon.

Business is going well, so nothing to complain about you'd think. ONE+, UP and UPPER sales continue to growth, we're still managing to do that with just selling framesets, so it should be relatively simple. Despite that, the past months have been very frustrating, even to the point that maybe for the first time, there's been some irritation creeping in between Andy and I.

We've been working on two new models in parallel for quite some time now. Don't get your hopes up, this is nothing out of the ordinary and doesn't mean two new models will ever see the light of day. To give you an idea, the project names for these two are OPN-11 and OPN-12, meaning they were proceeded by 10 other projects. And yet there are only three models in the history of OPEN, the other seven projects were abandoned.

We've been working on two new models in parallel for quite some time now. Don't get your hopes up, this is nothing out of the ordinary and doesn't mean two new models will ever see the light of day. To give you an idea, the project names for these two are OPN-11 and OPN-12, meaning they were proceeded by 10 other projects. And yet there are only three models in the history of OPEN, the other seven projects were abandoned. You might argue that's a terrible score, 70% failure! And I presume it is, the way people (including myself) are wired nowadays. We profess to love risk taking and risk takers, as long as they succeed. But of course if success is guaranteed, it's not risk-taking! Even if you say "well, I love the risk takers who succeed because they clearly have something extra, others in their place would have failed", that still means they weren't taking a risk, they were merely taking a direction that would have been risky for others. So they might be very skilled, they might be visionaries, but not risk takers.

Anyway, enough philosophizing. And we're not exactly saving the world here, we're just designing bikes, trying to do that a bit differently and that means that from time to time it doesn't work out. Of course it also helps (or hurts) that we have the freedom to abandon projects, that we don't have bean counters telling us "you've spent a couple hundred grand on this project, you have to bring out something to earn it back".

Back to the story, the OPN-11 was very close to production. It's a model I am very excited about, a nice addition to the line-up and very different from what exists in the market.

Then just one week to pilot production start, Andy sends me a note: "Big problem, the chain touches the dropout". I can't understand it, but see the proof on Skype. We measure everything, but it seems within spec. I check the CAD, all good. We try a different rear wheel, it works. Of course that doesn't mean anything, there are lots of different wheel specs. We try the offending wheel in an UP, it works. But that dropout design is meant to have different clearances, so it doesn't mean much either. I'm going crazy! Two days later the solution, it's not our frame that is faulty, it's the cassette. Somehow it had a lip on it that prevented it from fully sliding onto the cassette body. What are the odds of a standard production cassette, produced by the hundreds of thousands, has one that is faulty and that happens to be the one that makes it into our frame-check stock? Very small I'd think, but I am happy this one was. Phew.

A few days later, another note: "Big problem, crank X doesn't fit". What the heck, how is this possible? We know not "everything" fits, we always play with clearances and design around a specific group of cranks, but this crank should fit, Yet its chainring wants to go where our chainstay sits. We call the crank maker, check the clearances, and confirm it should be no problem. It should have the same chainline as crank Y but yet that crank has tons of clearance. We check spacers, BBs, everything, again it doesn't make sense. Even more strangely, when we put a bigger chainring on, the clearance gets better!

Finally the crank maker comes back to us: sorry, the chainring was an old design, it somehow slipped through, and just by chance made it to us and we happen to have made it the one crank to answer all questions. We get the correct chainring, it all works.

So we sign off on the start of the pilot production. The next day I wake up to an email from Andy: "We have a big problem". With a Force/Eagle AXS setup, the chain hits the chainstay. I'm not worried anymore, I'm sure it's a false alarm again. But on Skype I cannot deny it looks bad. It's not off by a little, it doesn't fit AT ALL.

I can't understand it, there is nothing special about that combination other than that it's new (meaning we didn't have the chance to try it before). But it should have more clearance with its long cage, not less. I'm frustrated beyond belief, this model could have been on the market within 3 months and now it's back to "indefinite". Is it the drivetrain parts that are wrong, or is it really the frame?

I feel Andy is frustrated too, and although he doesn't say so, I really feel this one is on me. I'm the one responsible for the designs, I should have caught this, but at the same time I am not sure how since none of our models indicated this combo could be an issue. And worse, I don't really see a solution.

For Andy it is maybe also a a bit of death by a thousand paper cuts. Because he does all the operations, most of the problems land on his shoulders. Delays in production, problems with retailers, a shipment stuck in customs, a painter gone mad, accounting (of any type), he has to deal with that while I get to play with bike designs. In my mind, I keep hearing "You had one job!!!!"

I take four hours just to sit on the couch while my mind is racing, and come up with two possible solutions. One that would save most of the molds and fixtures we have already made (about 30 in total), and one that would be better but would require most of the tools to be either modified or scrapped completely, which would obviously increase the costs but also the timeline to completion.

As I sketch it out and start working through the two options with our CAD designer, the second option starts to look better and better, in fact the frustration gives way to excitement. The new design is better than the old, and just before midnight we have the design ready. Off to the factory, so they can see if it is feasible, and I go to bed. The next morning, the factory is enthusiastic, they say they can probably make the new molds and the layup changes in six weeks, not as bad as I feared. They don't have the bill yet for what all the changes will cost, that's a part I am definitely not excited about. But to be fair, the success of the UP allows us to take risks even if it means we sometimes are presented with an unwelcome bill.

I show Andy the new design on Skype and share my excitement. I really am way more pumped about OPN-11 now than a week before. He tells me he had lost his excitement for this "model of hell", but with some workarounds he took the prototype OPN-11 for a ride and he is now really gung-ho again.

That day, our "resident videographer" happened to be in Basel because we thought we were going to shoot the final bike, so he went along for the ride and even took his drone. It was very cold but the snow was no match for the OPN-11. This was the result:

That day, our "resident videographer" happened to be in Basel because we thought we were going to shoot the final bike, so he went along for the ride and even took his drone. It was very cold but the snow was no match for the OPN-11. This was the result:And here we are, a few months down the road, a few days away from launch. And for the first time since December, I read this post again. Although I can still feel the anxiety from the week I just described, I also feel proud that the OPN-11 is finally ready. More coming soon.